When Dinah Lenney says, on page 20 of The Object Parade that “Every home should have a piano” I thought, this narrator and I will have little in common. She says this at the end of a short essay about the baby grand piano that she’s been lugging from coast to coast, that takes special movers to move, that is covered in framed photos that her housekeeper dusts for her.

I have never lived in a house with a piano, and as I’ve been sitting here drafting this book review, I’ve racked my memories—and I don’t think I’ve ever even been in a single family home with a baby grand piano. But wait, that’s not true—there was a grand piano in the home of that distinguished ex-pat translator and chorister who put me up for a couple of nights on short notice in Vienna. Which is to say that anyone can sound a little terrible out of context.

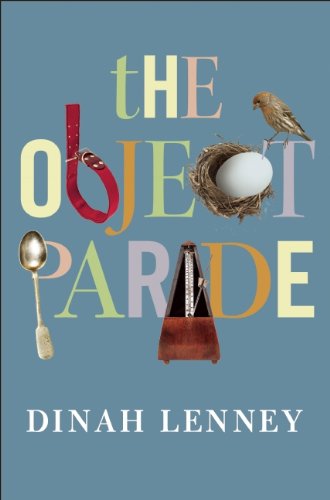

The Object Parade spoke deeply to me before I’d even cracked the cover, and my hopes were high. A memoir told through objects, one person told me. A catalog of the literal stuff of life, I could sum up the dazzling blurbs. Things, stuff, and lived lives—via flash essays. I’ve dreamed and day-dreamed this book!

And then there came the piano(s—there’s the one she grew up with, too) and a broken Tiffany watch, and some jade earrings, and the supporting role on a famous TV show that maybe or maybe not meant “little” to the narrator, and I thought, this narrator and I have never lived with any of the same stuff, and by stuff I am not just thinking objects.

Though Lenney and I did both have a broken acoustic guitar for awhile, the material intersections, otherwise, were few. For me it would be the Casio SK-1 I outgrew and handed down to my sister, an old Tom Peterson watch, mismatched onyx earrings, and that one time my voice was played on NPR News for 45 seconds.

And yet, I couldn’t stop reading. And as I did, I found ways in, over and over again. No, I don’t know what it’s like to bum around the upper east side in the late 70s, trying to make it as an actress while waiting tables and shopping for old linens and ancient sheet music, which are the circumstances that Lenney describes in the essay, “Flight Jacket”—but I know about leather jackets.

In the late 80s, I spent several weekends dragging my mother to every pawn shop in the “deep eastside” of Portland, Oregon looking for the perfect goth motorcycle jacket for under $135. Most were all wrong. Some had uncool patches or zippers that weren’t quite right—or horrors, were cut from brown leather instead of black. Finally, I found it: a classic cut, no fringe or silly logos, and ten dollars under budget. The only problem was that it was just a little bit too small. I was a “hefty” kid who had grown into an XL teenager. In the late 80s, there was no Torrid or Lane Bryant. Wearing XL in the 80s meant shopping in the “women’s” department or wearing men’s clothes. I didn’t want to admit that I was too fat for the jacket and so I bought it anyway. Spent all my meager savings on a coat I couldn’t zip up. It was not the first or last time that I told myself I could diet into some garment.

That jacket never did fit me, and when I think of it, I remember the deep shame of being fatter than I was supposed to be so much more than the pride of a cool ass leather. Lenney’s own jacket gives her a chance to think about the kind of parents she had, and the kind of parent she is—the jacket is more than just dinner and a show on 14th street, more than the seamstress who almost refuses to repair it.

Again and again, Lenney pinpoints and then examines all the ways that things decorate, populate, and demarcate the places and moments and pieces of a life. From a craft perspective, the concept of memoir as litany is (I can’t think of a better word for it) meaty. If you teach writing, this book might just inspire a handful of new prompts. And she has nailed the title, because all this stuff does roll past the mind’s eye just like a parade, once you get to musing on it.

Try it. Imagine the things that matter to you. First, the big stuff, they trundle past like be-flowered floats with their own dance tracks: the quilt my grandmother made, my old snowboarding jacket, a yarn winder and wooden swift, horse skull, clay sculpture of a seated woman, two teal lamps with black and white shades, mismatched dinner service for four, two red vinyl chairs and a chrome and melamine breakfast table. Then come troops of small things, like Shriners on ATVs, jugglers, or a clown on a unicycle: an old enameled pin shaped like a cockeyed dog, a small pink ceramic horse in the style of a Roman charger, a gray rock the size of two finger knuckles that is shaped exactly like a peanut, a green beetle carcass, two blue and white espresso cups, a ball point pen on which you can play a very tiny but accurate game of Operation, a bunny-shaped piggy bank painted all over with turquoise stars, a set of three palm-sized crocheted bears of the Mama, Papa, and Baby bear variety, a newspaper clipping with a picture of me pouring coffee at Fuller’s in 1991, plus one of the brown coffee cups that I’m filling in the photo. Then, after the floats and motorcades and rodeo princesses, come the books. Like the sudden crowd of a marching band, there are so many more of them than shelves in which to store them; files and boxes full of old letters, cards, pages torn from magazines, notes once passed in class. I’m sorry to say that I lost my own broken watch years ago, but even that’s still there in my mind’s parade, along with other lost items: a stable of Breyer horses, the foot-long taxidermied alligator dressed like a bride, a chunk of raw turquoise, stacks of rockabilly CDs, a tufted green side chair, Fugazi t-shirt: every damn thing, a story.

While The Object Parade is ostensibly about stuff and things, it is really about Lenney’s life: her relationships, her progress. It is that narrative thread that hooked me and then led me through the book, giving me space to connect with Lenney. She has difficult moments as both a mother (“Flight jacket”) and a daughter (“Green earrings”); she wants people to like her and appreciate her efforts (“Chicken stew”); she has complicated relationships with her siblings (“Nests”). She gets obsessed over little things, like an old coffee scoop or the age limit for certain outfits (“Scoop,” “Little Black Dress”). And the whole parade culminates in a beautifully honest and reflective moment that I will not spoil here. When I finished, though I had read several concise and sharp essays about objects, what I was struck with most was Lenney’s accessible humanity. As it turns out, though she and share few things, we have a ton of stuff in common.

Verdict: RECOMMENDED (and the garage sale will be next Saturday, too, from 9-4)